By Mira Harvey

This year, GRS 482A gave me the opportunity to poke around (virtually) in Medieval garbage from the site of Ancient Eleon. I worked on a late 15th or early 16th century CE refuse pit, which is informally known as “Graham Pit” after the University of Victoria alumnus who had the opportunity to dig it as a member of the Eleon excavation team. While I was able to find helpful comparanda for similar pits at Thebes, I wanted to understand why this pit was dug – beyond just analysing the finds inside. What was the intention behind its construction and abandonment? Digging a refuse pit in a certain location is a deliberate choice that the inhabitants of the Eleon acropolis made. Understanding why that choice was made can help us imagine what daily life at Medieval Eleon looked like and lend agency to peoples in the past.

Graham Pit (Figure 1) is located on the eastern edge of the Eleon acropolis in the Archaic and Classical period ramped entrance. Other Medieval remains in the vicinity, including some poorly preserved wall fragments, may suggest a small household existed nearby. The pit is roughly circular clay-lined, and tapers slightly towards the bottom. Unlike other Medieval pits excavated at Eleon, which appear to have collapsed in antiquity, the lining of the Graham Pit is well-preserved.

Refuse pits are relatively common at Greek archeological sites. They are typically described as pits containing assorted trash (e.g., animal bones, shells, pottery, rocks) dug in sterile earth. When investigating Graham Pit, I first looked at similar refuse pits from Thebes and compared the ‘garbage’ inside. This analysis showed that the pit from Eleon was part of a wider Boeotian practice and chronologically similar in date. By taking a closer look at the construction of the pits, however, I realised that at least some of these pits may have been designed for a rather specific type of waste.

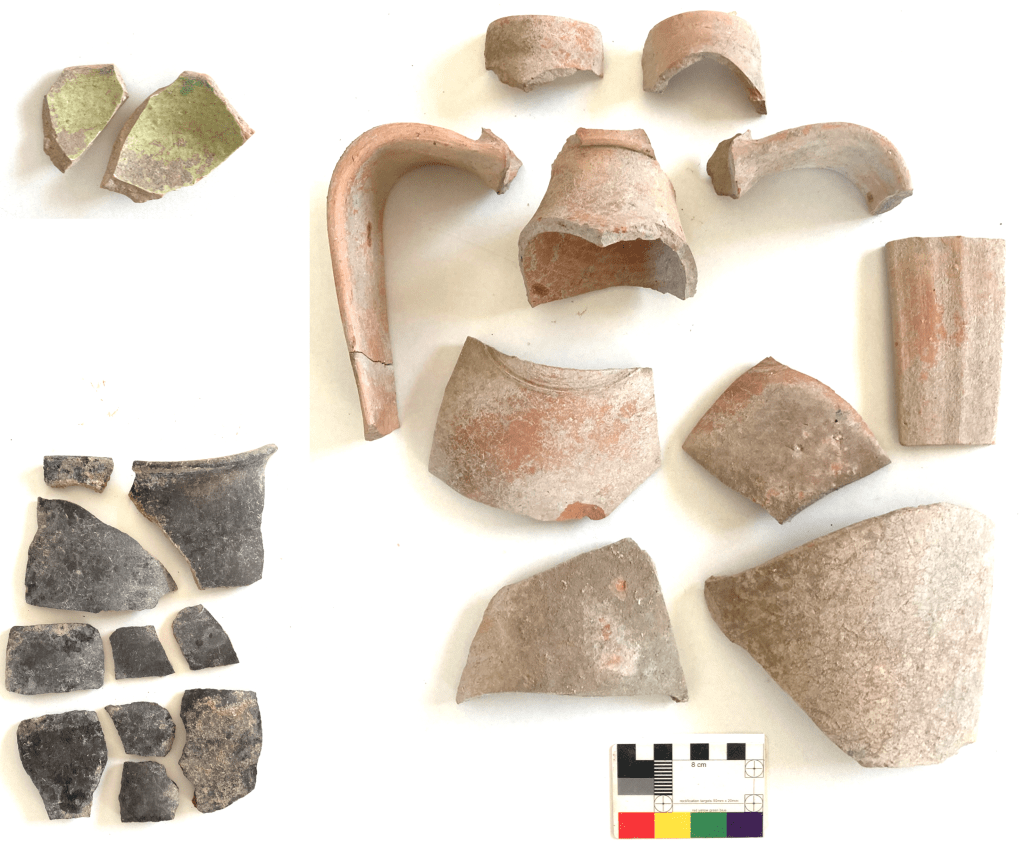

Excavations showed that the pit was intentionally filled at the end of its use-life. Finds from inside the pit include mendable pottery, an incised copper alloy bracelet, and rare earlier pottery fragments, most from the Classical and Hellenistic periods. At the very top of the pit, a large green-glazed Medieval sherd was found, helpfully providing a terminus post quem for the closing of the pit. More sherds belonging to mendable or almost-mendable vessels continued to be found into the middle layers, usually smashed on the rocks below. These sherds belonged to a cooking pot, the same green-glazed bowl, and an undecorated amphora (Figure 2).

Late Ottoman refuse pits from the Pelopidou Street excavations at Thebes are similar to Graham Pit. They were filled in a relatively short period of time, generally with kitchen waste, animal bones and construction debris. The number of pits at Thebes indicate a dense population, consistent with census data that shows the early Ottoman period was a prosperous time for Thebes, whereas Eleon, a small agricultural village, has preserved only a few pits clustered in the northwest trenches and the ramped entrance. The finds from the Theban pits are also wealthier than Graham Pit, but there are also many similarities. Most of the ceramics from pits at Thebes are undecorated, unglazed narrow-necked jugs and cooking pots, much like the unglazed cooking pot and amphora in Graham Pit. Additionally, domestic items made of wood, basketry, leather or other perishable materials were likely present in Graham pits but have not survived.

While these finds can tell us about a population, its relative size, and wealth, I wanted to zoom out and think about the everyday purpose of refuse pits. If Graham Pit was only for general waste, the easiest way to get rid of garbage is to simply remove it. Why would the residents of both Thebes and the Eleon acropolis choose to spend time and energy digging holes, effectively in their front yards, to dump their garbage rather than simply remove it elsewhere? The location of the pits may indicate a need for quick, convenient disposal of waste… maybe waste of the human kind. Convenient bathroom facilities were just as important in the past as they are today!

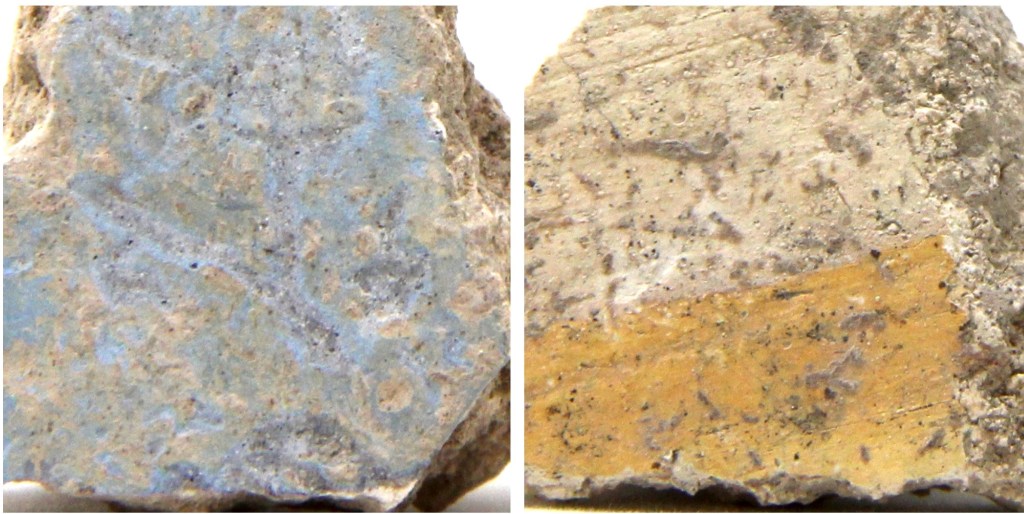

This led me to investigate Graham Pit’s possible use as a cesspit for the Medieval residents of Eleon. The clay-lining of the pit lent itself to this hypothesis, as well as the fact that it is shallower than other Medieval pits from Eleon and Thebes. Waterproofing cesspits with clay had practical benefits, such as keeping the waste from seeping into the soil. Cesspits (Figure 3) were typically emptied of waste and reused, as it was impractical to dig a new cesspit each time you filled one. Lining a cesspit with clay would have helped clarify the boundaries of the pit and assisted in efficient removal of the waste. Clay-lining further indicates that on some level, the pit was designed by its creators – not just a hole dug and filled and forgotten.

Cesspits may not just have been solely for human waste disposal. Human excrement and organic waste is fantastic fertilizer, something well-utilized by farmers in both the past and present day. In Medieval Haarlem and Bruges, extant documentation even reveals that farmers paid townspeople for the privilege of emptying their cesspits for the fertilizer inside! In a small agricultural village, such fertilizer may have literally been worth its weight in gold! We might imagine a world then where the contents of Graham Pit were emptied, composted and then applied to the surrounding fields or gardens between small households.

Because Graham Pit’s fill is relatively homogenous and the pottery is mostly mendable, it was likely filled in a single episode when its creators decided to end its life. It may have gotten too smelly, or too old, and the location of the ‘bathroom’ was changed. We can think of the fill as a structured deposition, since we can trace a series of clear steps that led to its closing. First, a layer rich in rocks from small to large size, perhaps originally including organic materials. Next, other household garbage was added including large ceramic fragments that broke on the rocks below. Finally, the pit was covered with a roughly circular cap of field stones. The cap of stones may then have served as a visible reminder of the pit and prevented another pit from being dug in the same location. Similar markers above the other Medieval pits at Eleon, show that this was part of a wider strategy on the part of the inhabitants to mark out the subterranean landscape of the village.

Medieval pits in general warrant further study, not just of their contents, but of their locations, designs and purposes. In other words, rather than focusing on the meaning of the contents, we instead focus on why the pit was created, how it was used, and the broader effects of this practice. Working on Graham Pit was an incredible opportunity to work on material culture that has not yet been formally published. In my first year at University of Victoria, I was able to visit Eleon through the Semester in Greece program, and it was exciting to be able to return by studying material culture from the site. One of the reasons I love archeology and history is the ability to imagine and illustrate daily life in the past. Investigating the waste management practices at Medieval Eleon allowed me to do that firsthand.

Image Source:

Hall, A. R., and H. Kenward. 2015. “Sewers, cesspits and middens: A survey of the evidence for 2000 years of waste disposal in York, UK,” in Sanitation, Latrines and Intestinal Parasites in Past Populations, ed. P. D. Mitchell, Burlington, pp. 99-119.